Teaching

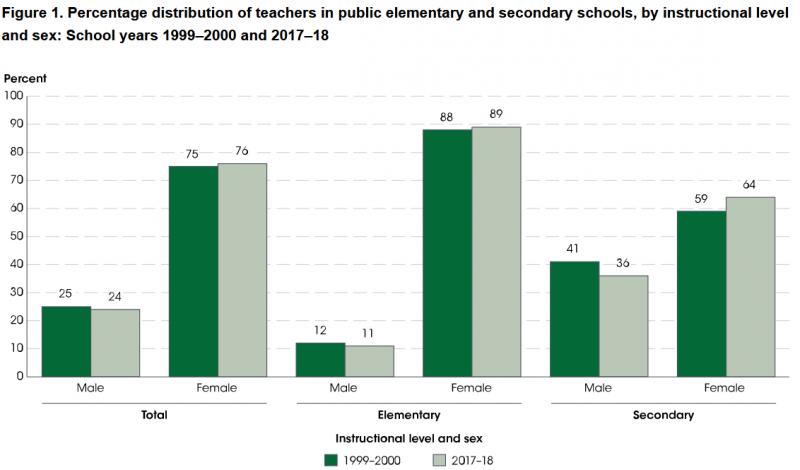

Of course, an analysis of academia would not be complete without focusing on one of its core elements: teaching. Statistically, women tend to make up a higher percentage of teaching positions in pre-university education. A study done by the National Center for Education Statistics shows that the percentage of male educators have actually declined between 1999-2000 and 2017-18 in pre-primary, primary, and secondary education. At the university level, however, this trend is reversed. A summary of global data by the nonprofit group Catalyst shows that not only do women hold fewer senior academic positions in universities in Australia, Japan, the United States, and many countries in Europe, but they are often paid less for their work as well.

However, this is not to say that women who are given the opportunity to hold higher-ranking or tenured positions in academia do not perform fulfilling work. Here, Kirtly Parker Jones, PhD describes how she feels she is engaged in constant growth as an educator, even though she has stopped teaching through more traditional avenues at the current point in her career.

"I was a TA when I was in college, and when I was a resident, I taught Harvard medical students. That's because we all did give lectures and had students with us. When I came here, we were a very small department, and everyone has students with them all the time... so you're teaching every day. It's not like in undergradutate school [, where] people teach, they have a couple of courses that they teach a year... we [had] students with us 24/7. Every time we [were] at the hospital, we [had] students with us.

Now I'm not teaching that much. People will ask me to give a guest lecture, which I usually do three [to] four [to] five times a year. I used to travel a lot to teach for post-graduate courses. But now I have a podcast (The Seven Domains [of Women's Health]). I have about 300 short podcasts there, [each] about 10 minutes and now [I] have about 12 half-hour podcasts. And so that's a teaching opportunity.

I think [teaching has] been a way of learning new things, so being an educator means you keep learning new things. You don't get to just teach the old stuff. And presenting something that you think is magic and wonderful to someone so that they see it in a new way...makes it all new to you again."-Kirtly Parker Jones, PhD

S. Mckenzie Skiles, PhD also describes how she finds teaching incredibly fulfilling. She loves watching her undergraduate and graduate students grow in their scientific thinking and understanding of the world around them.

"[My] favorite part of my job is advising students and getting to watch them sort of start a project, sort of formulate ideas, and then carry through on the project, and then gain skills on how to actually approach something scientifically and sort of start thinking more critically about the world around them. They can gain those skills doing something, snow or hydrology related and then take it elsewhere. [... F]requently, I spend the most time with my grad students, but that can also grow undergrad projects as well. And it's just, I think it's really fun to watch students [...] grow, grow and become more independent thinkers on their own and [...] take ownership of their own ideas or just become more confident in doing research. [...] That's the favorite part of my job." -S. Mckenzie Skiles, PhD

Cynthia Burrows, PhD also cites a young environment and constant student turnover as her reason for teaching at a university before her career took a research-oriented turn. It seems that even as educators, there is still learning to be done.

"I like universities because there are perpetually young, bright students. They get four or five years older, you can watch that, but then there's this constant new crop coming in. And so I liked that. I liked that they're young, that the environment is young. And I also felt like I didn't know enough to go out in the real world. I needed...to know more. I was still learning." -Cynthia Burrows, PhD

However, there are unique challenges when it comes to teaching. Especially within the first year that students arrive at institutions of higher learning. Students might need different amounts of time or support in order to make the necessary transition from secondary education to college. Sometimes the class size of introductory courses make it difficult for professors to directly address the needs of every student.

"Let's say [it's for] a large lecture course, and I'm often doing large lecture courses, whether it's organic or biochemistry, then there are a lot of students out there. And the question is are you, are you being fair in your delivery of material, helping them learn?

And then, you know, the unpleasant part is we have to give exams and we have to give grades at the end. So that is always an ongoing challenge... I mean, the good students can also can often do well, no matter who the instructor is and what the method is, whether it's traditional lectures or flip classroom, a good student will almost always do well. And a poor student can really struggle in those.

But you know, on the other hand, if you teach to the lower tier of the class then you are, maybe you risk losing the upper tier of the class, who are the great students that you want to motivate, right? You want to inspire [them] to go on and do other things. So finding that balance between extremes is really challenging, uh. But what I like about it is that every once in a while there is a personal interaction that really pays off." -Cynthia Burrows, PhD

Large and often less personal class sizes, along with the new social environment of a university or college may lead to a student falling behind in a class, even if they did well in traditional learning environments prior to entering college. Chemical Education researcher Regina Frey has studied different styles of learning in regards to this problem, and suggests that a growth mindset is very useful in helping underrepresented or minority students succeed. A growth mindset is a way of viewing intelligence or understanding of material not as a fixed limit among students, but rather as a constant, evolving practice. By using the growth mindset in a random-assignment classroom experiment among entry-level college students who were taking General Chemisty 1, Frey and her partners found that achievement gaps between minority and majority students were minimized, or in some cases, completely eliminated.

Even educators themselves can learn from this practice—Cynthia Burrows, PhD recounts a very positive experience with a teacher's assistant in graduate school that influenced her flexibility in approaching problems she didn't understand immediately. While she does not explicitly mention a growth mindset intervention, it seems this method is useful even when it is not purposefully implemented by name. A growth mindset is important because it can encourage students to achieve, especially women or students who have historically been told they are less capable and intelligent than other students."Because I had, you know, the super TA in my first year of graduate school, one thing she taught us was, you know, she said sometimes students ask a question and your immediate response's to say, I don't know. And she said, just stifle that, don't say it, go to the board and say, well, here's what we know and rewrite the problem, redraw it out and start just thinking out loud.

"The fact is you probably do know the answer. That did a world of good for me, that approach. I realized that, yeah, I probably do know the answer in the end, even though my first response may well have been, I don't know. Oh my gosh. But that, that helped me a lot, even in, you know, a lot of research areas where someone will ask a question and you're thinking: oh, I never thought about that before. But instead of saying that, you kind of restate the question and then go on to say, well, here's what I do know about that area. And therefore, maybe I can answer this question, you know? So, so that was pretty helpful." -Cynthia Burrows, PhD

When this growth mindset is paired with a challenging curriculum and a supportive environment, women and other minorities have the opportunity to succeed in STEM fields. Holly Sebahar, PhD found that this teaching philosophy gave her the tools she needed to succeed when she was in school, and now, she uses this philosophy with her own students.

"I think I got the most out of the class when I was really challenged when the bar was set extremely high, maybe higher than I thought I could get over it. I think that was the ideal place, […] just barely above where I considered myself having the potential to reach […] then, having a really supportive environment of, you know, the teacher creating an environment which said, ‘I want you to succeed, I want you to do well’ [...] then providing the resources to actually make that possible. So [creating] a challenge but providing the support network so that as many students as possible can kind of make it to that end goal. You know, I do my best to try to challenge students enough, but not too much, not too little. I think there's a sweet spot in there where you feel like [...] it's hard, but doable, right? So it's sometimes– even during the semester, I have to really change the way I'm writing exams or worksheets depending on this specific class, right? [...] How well are they taking in this information? It might be different than the one before."

Teaching is a massive accomplishment in any academic's life. The required mastery of a subject is a huge feat that does not get the recognition it desevers. For some women, incorrect suffixes and the prioritation of underqualifed males as an alternative to a female academic are a reality to the profession. S. McKenzie Skile, PhD says,

"I think that all women professors probably get not being recognized the same as our male colleagues. And this is usually small things like not being called Dr. Skiles or Professor Skiles but being called Ms. Skiles. And that I try not to let that bother me too much but you just wish that students would just not treat women and men professors differently but it's something that I just try to politely correct or just say at the beginning of the semester, I prefer to be called Doctor or Professor Skiles or just McKenzie. They'll use either one of those. Just call me by my first name.

The comfort level of people being willing to ask for help or like trust that you can provide help has been an interesting aspect of this that I didn't really expect. I will sometimes have a male TA and students will ask the male TA for help before me, they're like, oh, well, I just thought he would be able to help me. And I don't know if that's a perception of like maybe they're asking him because they think that he has more time, but also I wonder if they're asking him because he’s a male. So it's hard to like really understand where that's coming from. But I do feel like there's some differences in the way that female professors are treated by students and not all students but enough for it to be obvious to me."

These challenges illustrate a lack of respect for female professors, especially when comparing Sikes’ academic experience with that of her male TA. Her expression of a noticed deficit between the respect given to male and female academics is alarming and illustrative of a patriarchal system.

Page written and researched by Abigayle Kendall, Kaylee Martin, Rachel Nelson, Eva Quintus-Bosz. Edited by Simon Lee and Lily Jones.

Later Edited by Pamalatera C. Fenn