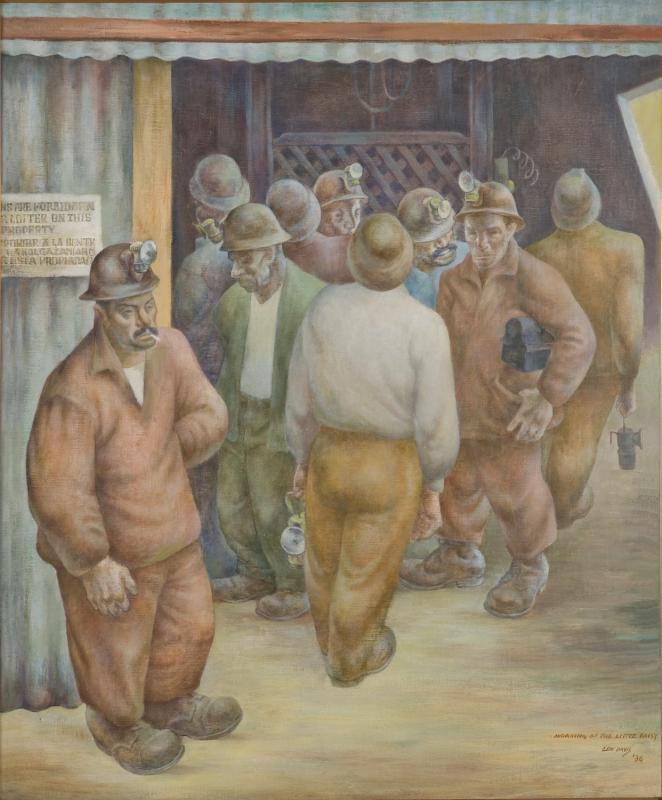

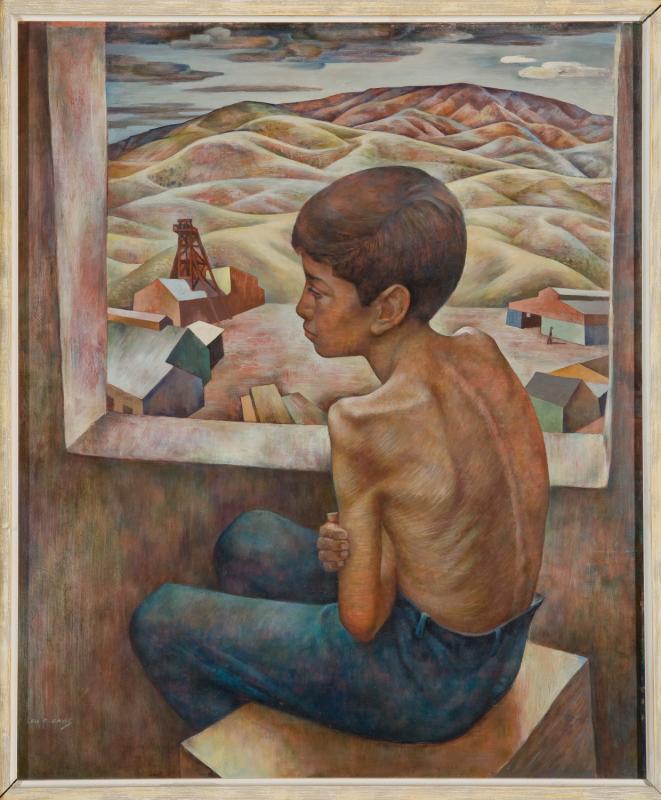

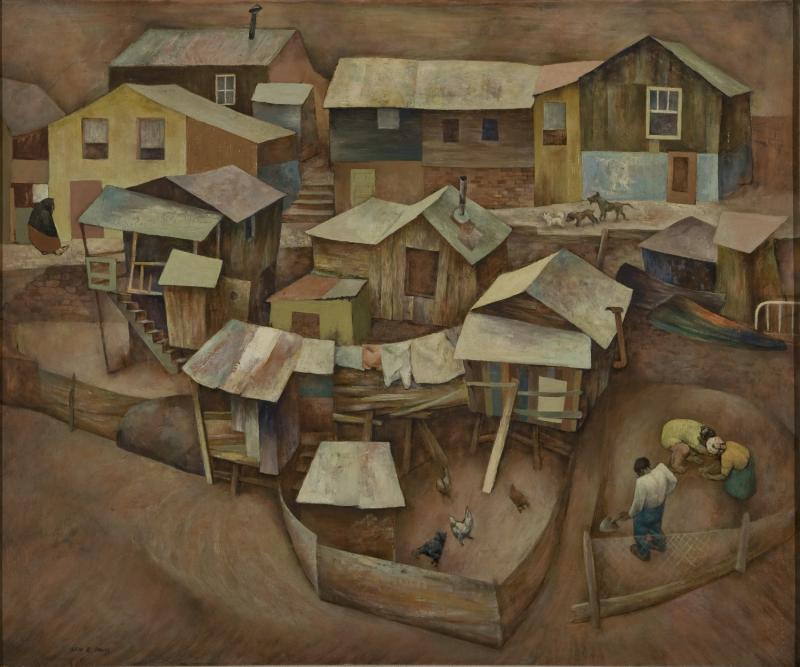

Arizona’s most notable artist of mines was Lew Davis (1910-1979). Born in Jerome, he knew well the grim realities of a mining community, as his father was employed as a carpenter for a local mine. In 1927, he left Arizona for New York to study art. His strong figurative skills were honed by his studies at the National Academy of Design, and while his style was representational, he stylized and simplified details, which resulted in strong canvases. He returned to Arizona in 1936 during the depths of Great Depression, which had a devastating effect on the state’s mining communities.

When WPA support became available, administrators encouraged artists to return to their home states, and back in Arizona, Davis began to explore mining as a significant theme. His works depicting labor were sympathetic and attuned to the reality of life for the miners. The support he received from the government meant that he did not have to go to work as a mucker, as he recalled: “Two more weeks and I would have been down in the mines.”1 The work he would have been hired to do was back breaking and exhausting, as the job consisted of loading ore that had been drilled and blasted into cars to be hauled up to the surface.

1 Janet Stewart, “Depression Art of Arizona and New Mexico,” Southwest Art, vol. 11, no. 4 (September 1981): 113.