The Copper Kings: Arizona, Utah, and Montana

Rolling Up the Score in the Copper Bowl

More than three decades later in November 1952 Ansel Adams’s image of the Bingham Canyon mine was published in Fortune magazine as an advertisement for the Kennecott Copper Corporation. The ad copy took a sports theme:

"They’re rolling up the score in the 'Copper Bowl': It looks like a stadium for giants. Its 'seats' are 65 feet wide. 70 feet high. It stretches a mile and a half across. It is the largest open-pit copper mine in the world—the Kennecott Utah Mine. And in this 'Copper Bowl' a team of drillers, dynamiters, shovel operators, locomotive engineers, and other workers all pull together to get out the ore. Together they produce about thirty percent of all the copper mined in the United States—more than one half billion pounds a year. That’s a 'score' Kennecott is proud of. And it means a lot to a nation that depends so greatly on copper for industry and for defense." 9

Martin Stupich’s photograph of Bingham Canyon taken after the huge landslide of dirt and rock on April 10, 2013, records the aftermath of what was “probably the biggest nonvolcanic slide in North America’s modern history.” (Figure 8) Two separate slides lasted a total of three minutes, releasing nearly one hundred cubic yards of debris moving at speeds of up to one hundred miles per hour. This would have been enough “to bury Central Park 60 feet deep.”10 His image presents a weirdly disrupted landscape that completely disorients a viewer’s directional senses.

Part of a series on Re-Manifesting Destiny, Erika Osborne’s (b. 1978) sublimely apocalyptic The Chasm of Bingham (Figure 9) presents a smoking primordial landscape. Her image is deeply imbued with the spirit of her nineteenth-century male predecessors whose “work helped bring about: the boom of industry, development and growth, and all its subsequent issues that we continue to see today.”11

5 Utah: A Guide to the State, 121.

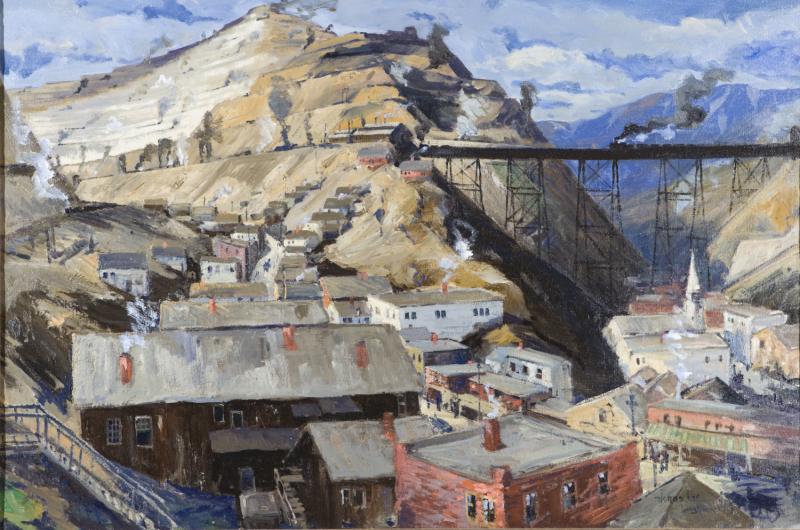

6 Jonas Lie to Daniel Cowan Jackling, April 10, 1917, Daniel Cowan Jackling Papers, Department of Special Collections, Green Library, Stanford University, Collection Number M0093, Box 28, Folder 9.

7 F. Newlin Price, “Jonas Lie: Painter of Light,” International Studio 82 (November 1925): 107.

8 Jonas Lie to Daniel Cowan Jackling, April 10, 1917, Daniel Cowan Jackling Papers, Department of Special Collections, Green Library, Stanford University, Collection Number M0093, Box 28, Folder 9.

9 Jonathan Spaulding, Ansel Adams and the American Landscape: A Biography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995): 264–65.

10 Deanna Conners, “Today in Science: Bingham Canyon Landslide,” EarthSky, April 10, 2019. Accessed March 27, 2021.

11 See the artist's website