Mining towns were distinctly insalubrious places, as notable photographer Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916) discovered when he arrived in Butte in July 1890. He wrote to his wife from that rough town: “here I have been sitting since trying to peer through the smoke which is thick enough to cut.”12 The weather was “hot, dusty, windy—a gale—and so smoky that from the Hill you can’t see the town and from the town you can’t see the Hill.”13 By September, it was raining hard with howling winds and “as cold as Greenland.”14 As a result, his work underground progressed slowly. He remained in Montana until mid-October: “I am still at this horrible hole. Froze up or nearly so. There is no fun in it. There has been continual snow and wind and hail and sleet and every other detestable element of weather.”15

Butte was another major center of the American copper industry; the mines were in Butte, with the smelter in Anaconda about twenty-five miles away.16 One writer noted that “the Butte citizen’s blood pressure rises and falls with the price of copper. . . . Sometimes he is half-convinced that Butte is the real capital of the United States and copper instead of gold the proper standard of values.”17 Butte is the county seat of the region and, at the time, was responsible for “seventy percent of Montana’s exploited mineral wealth.”18

Some seven thousand men were employed in the mines, and their eight-hour shifts underground varied little from day to day. After changing into work clothes in the mine’s locker room, they waited for the cage that would transport eight tightly packed men downward at a rate of eight hundred feet per minute to where they would work that day. They would pass long trains of ore cars shuttling ore to the huge bins that hoist it to the surface. Trains then hauled it to the smelter. The mines were noisy: in addition to the drilling and blasting noises, the pumps forcing water up from the lower levels of the mine to the surface sounded “like a great, steady pulsebeat deep in the earth.”19 More racket came from the air-driven drills that “stutter like machine guns as they bore into the rock half a mile or more below surface. The men who operate the drills set the explosive charges, and muck (shovel) the ore into chutes, work strenuously and often under trying conditions.”20

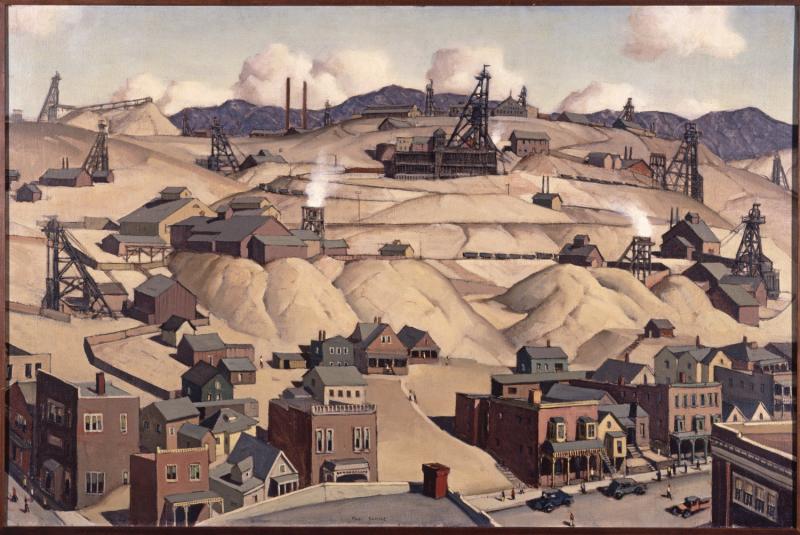

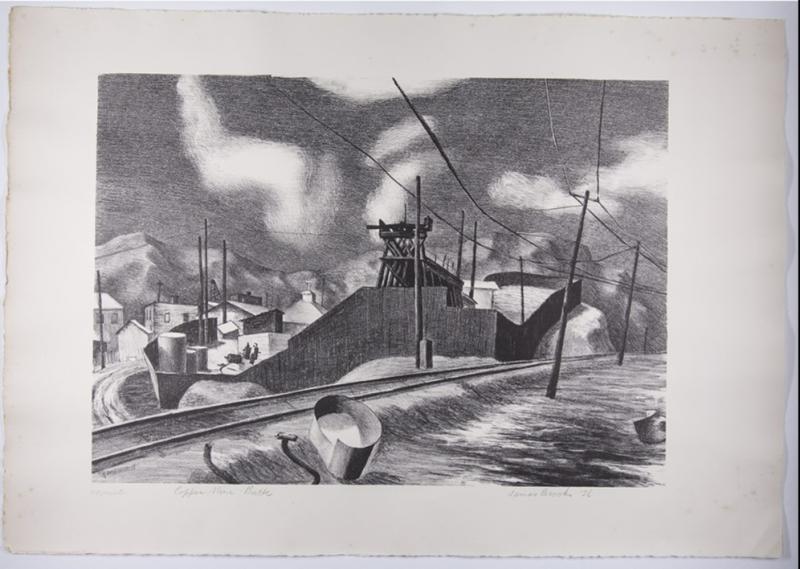

Fortune magazine regularly reproduced the work of important American artists, as well as commissioning new work, and in 1936 the magazine hired Paul Sample (1896-1974) to produce a series of eight paintings depicting the operations of the Anaconda Copper Company in Butte, four of which survive. Published in the December 1936 and January 1937 issues, these paintings include Butte Hill as Seen from Butte City. (Figure 10) The town’s buildings convene pleasantly in the foreground, with the busy mining operations behind dotted with gallows head frames. Sample’s strong image literally maps the town. The ore mined in Butte was smelted in Anaconda, twenty-seven miles away. While the smoke from the stack—then the world’s tallest—polluted the air and killed all nearby vegetation, for those employed in the smelter the “smoke means life itself to the town.”21

13Letter from CEW to his wife, Frances Sneed Watkins, July 27, 1890, in Carleton Watkins: Selected Texts and Bibliography, 61.

14Letter from CEW to his wife, Frances Sneed Watkins, September 5, 1890, in Carleton Watkins: Selected Texts and Bibliography, 61.

15Letter from CEW to his wife, Frances Sneed Watkins, October 15, 1890, in Carleton Watkins: Selected Texts and Bibliography, 65.

16 Because of the pollution they generated, the smelters were generally situated some distance from the mines. In Arizona, Bisbee’s was in Douglas, and the Clarkdale smelter served the mines of Jerome.

17Federal Writers’ Project (WPA), Montana: A State Guidebook, (New York: The Viking Press, 1939), 8.

18Montana: A State Guidebook, 12.

19Montana: A State Guidebook, 146.

20Montana: A State Guidebook, 80.

21Arizona: The Grand Canyon State, A State Guide, 180.